Investigations aim to evaluate ovulation, tubes and sperm.

Tests for ovulation:

A number of tests have been proposed for determining whether ovulation is occurring. Some, such as basal body temperature charting and cervical mucus testing, are not very reliable and not routinely used any more.

One of the most common tests used is a blood test for measuring serum progesterone. The timing of this blood test needs to take into account the length of the woman’s menstrual cycle. Progesterone levels should be tested when they are expected to be at their highest, which is usually around 1 week before the start of the next menstrual bleed. This means that for a typical 28-day cycle, the blood test needs to be performed on Day 21 (hence the reason this test is often referred to as a Day 21 Progesterone). The timing of the test will be different for other cycle lengths. For instance, for a 32-day cycle, the appropriate time for the test is Day 25; doing the test on Day 21 will give a falsely low result. Other tests for ovulation include ultrasound monitoring and LH kits for testing urine. For more information, see my section on The Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Tracking.

Sperm tests:

A man’s sperm is tested using a test called a semen analysis. Sperm tests are used to try to predict the ability of the sperm to fertilise the egg.

To do this test, a man needs to ejaculate into a sterile plastic pot and take the sample to an accredited andrology laboratory which will determine a number of different features of the sperm. Semen analyses evaluate sperm features in the sample against stringent criteria set by the World Health Organisation (WHO 2010).

For reliable results, it is critical that semen production is performed properly:

- The male should abstain from ejaculation for 2-7 days prior to the test

- All the sample should be collected into a wide-mouth sterile plastic container

- The sample must be delivered to the lab within 45-60 minutes of production

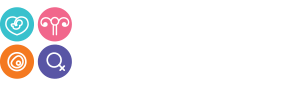

A number of parameters are analysed in the semen sample. The three key ones are:

- Sperm concentration which should be greater than 15 million sperm/millilitre

- Progressive sperm motility (or the proportion swimming fast in a straight line) which should be 32% or more

- The proportion of normally shaped sperm (or normal morphology) which should be 4% or more

Tests for tubal patency:

Tests for tubes aim to determine whether tubes are open (or patent). It is important to stress, however, that Fallopian tubes do not simply act as passive conduits for sperm, eggs and embryos. Tubes provide the proper mix of nutrients required for sperm, eggs and embryos. Tubes also possess very fine hair-like processes on their internal surface (known as cilia) that “walk” the embryo towards the womb cavity. Therefore, a test that shows tubes are open doesn’t necessarily mean those tubes are fully functional.

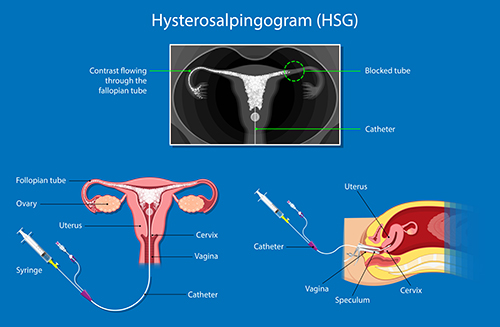

HSG: One commonly used test for evaluating tubal patency is a Hysterosalpingogram (HSG). This is an X-Ray test. It is performed without an anaesthetic and involves placing a tube into the neck of the womb and injecting radio-contrast dye through the tube into the womb cavity. A series of X-Ray images are then taken in order to track the flow of dye through the womb and tubes. If the dye is seen flowing through the entire length of both tubes and entering the pelvic cavity this means that the tubes are open. If the tubes are blocked, the dye may accumulate in the swollen ends of the Fallopian tubes; a blocked and swollen tube forms what is known as a hydrosalpinx. HSG’s can also identify fibroids and polyps, which show up “filling defects” in the womb cavity. For more information see my sections of Fibroids and Miscarriage and Recurrent Miscarriage (section on “Problems with the womb”).

HyCoSy: Another approach for investigating tubal patency is called HyCoSy (for Hysterosalpingo Contrast Sonography) and involves using ultrasound. Similar to HSG, HyCoSy involves placing a tube at the neck of the womb and injecting a liquid, which can be detected using ultrasound. The ultrasound examination can also provide other important information at the same time such as identify fibroids and polyps, determine whether the womb shape is normal and estimate ovarian reserve by counting antral follicles (see below).

Laparoscopy and dye: The third way to evaluate tubal patency is via a laparoscopy and dye test. This is the most invasive and expensive approach but is also the most reliable. It requires a general anaesthetic and involves keyhole surgery to visualise the Fallopian tubes directly. Blue-coloured dye (Methylene blue) is then instilled through the neck of the womb. Using the laparoscope, blue dye will be seen coming through the end of the tubes if they are patent. This is the only approach that directly looks at the tubes and allows their condition to be carefully inspected. It also allows for any co-existing conditions like endometriosis or scarring from prior infection to be treated at the same time, and allows surgery to be performed to unblock tubes. It also allows very badly damaged and swollen tubes (hydrosalpinges) to be removed prior to embarking on IVF treatment. This is important since hydrosalpinges markedly reduce IVF success rates by around one half.

Estimating egg numbers:

Sometimes, as part of the infertility workup, a test for estimating how many eggs are left (also known as the ovarian reserve) is performed. The most commonly used one nowadays is a blood test known as Anti-Müllerian Hormone or AMH. Ovarian reserve can also be estimated using ultrasound scanning to count the numbers of small antral follicles. For more information on AMH and ovarian reserve, see my section on AMH, Ovarian Reserve and the Egg-Timer test.