The main participants involved in producing sperm in the ejaculate include hormones (FSH, LH and testosterone), the testicular spermatogenic machinery and the ducts leading from the testes to the penis.

Sperm abnormalities can therefore result from problems with:

- Sperm production (or spermatogenesis) in the testes

- The transport of sperm from the testis to the penis

In the most severe cases, there is a complete absence of sperm in the ejaculate, a condition referred to as azoospermia.

Environmental and lifestyle factors:

In 65-80% of cases of sperm abnormalities there is no obvious cause. In these instances, there is an inherent problem in testicular spermatogenesis. It is believed that environmental factors (e.g. pesticides, “endocrine disruptors” etc.) and/or lifestyle factors may be important contributors.

In the Western world, these factors are having a major impact on sperm quality. Obesity, cigarette smoking and excessive alcohol intake have all been linked with poor sperm quality. A large study that analysed sperm tests from almost 43,000 men found that sperm counts had declined by a staggering 50-60% over the past 40 years in North America, Europe and Australia & New Zealand.

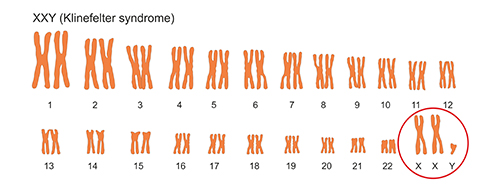

Klinefelter’s syndrome:

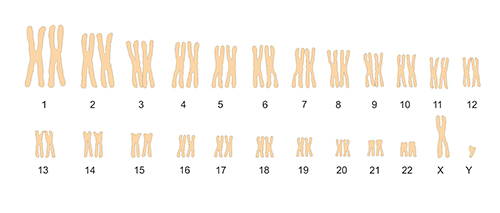

Reduced testicular spermatogenesis may be the result of chromosomal problems. The most common chromosomal disorder in men is Klinefelter’s syndrome, affecting 1 out of every 650 men. Human cells normally have a total of 46 chromosomes, made up of 22 pairs of autosomal chromosomes and 2 sex chromosomes; in males, the sex chromosomes are an X and a Y chromosome.

In Klinefelter’s syndrome, there is an extra X chromosome resulting in an XXY make-up rather than the typical XY pattern.

Men with Klinefelter’s syndrome often have small testicles and reduced levels of testosterone resulting in reduced body hair and muscle mass. It may also result in breast development, learning difficulties and behavioural problems.

Y chromosome microdeletions and genetic causes:

Reduced sperm production can also be the result of the loss of small segments from the Y-chromosome (known as microdeletions) before birth. Microdeletions in the Azoospermia Factor (AZF) region of the Y chromosome are well known to affect sperm production.

Alterations in genes such as SOX5, DAZL, TEX11, DPY19L2 and AURKC are also linked to sperm abnormalities.

Obstructive problems:

In around 5% of cases, sperm is being made in the testes but there is none in the ejaculate because of a blockage of one or more of the tubes leading from the testes to the penis. A frequently seen cause of blockage is a previous vasectomy. Blockages can also occur due to scarring brought about by infection.

Azoospermia may also be due to an inborn absence of the tube known as the vas deferens, which is required for transporting sperm from the testes (see “How is sperm produced?” above); this condition is known as congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD) and occurs in 1-2% of infertile men. It is estimated that around three-quarters of men with CBAVD carry an abnormality in the CFTR gene that causes cystic fibrosis.

Hormonal causes:

Problems leading to reduced production of the hormones GnRH, FSH and LH can impair spermatogenesis. Some of these may be present from birth whilst others may occur later in life, for instance, as a result of a brain tumour.

Undescended testes, varicoceles and hyperthermia:

Prior to birth, the testis travels (or descends) from a position within the abdominal cavity to the scrotal sac outside of the body via a canal in the groin area known as the inguinal canal. This position outside the body keeps the testes a couple degrees cooler than core body temperature and is crucial for proper spermatogenesis. In some cases, one or both testes become trapped in the abdomen resulting in undescended testis (also known as cryptorchidism). Persistent undescended testes occur in around 1 in 50 males. If the testes are not brought down into the scrotum, there will be poor sperm production due to the detrimental effects of the higher temperatures found within the abdominal cavity.

Other factors linked with increased testicular heat (hyperthermia) have also been implicated in poor sperm quality. These include varicoceles (dilatations of the spermatic veins), chronic sauna exposure, tight-fitting underwear and professions involving prolonged durations of sitting (e.g. truck driving).

Testicular trauma and torsion:

Trauma to the groin area, for instance, while playing sport, can cause sudden pain and swelling of the testes. In some cases, the testis can twist on its suspensory cord thereby cutting off its blood supply, a condition known as testicular torsion. Torsion is a medical emergency and if left untreated, causes permanent testicular damage.

Anabolic steroids, chemotherapy and other drugs:

Anabolic steroids are used by some athletes and bodybuilders. They shut down the body’s own production of FSH thereby stopping spermatogenesis (see “How is sperm produced?” above). Men who use anabolic steroids for extended periods of time develop severely suppressed pituitary FSH production and absent spermatogenesis. Sperm production can be very slow to recover after discontinuing steroids following extended periods of steroid usage.

Drugs used for cancer treatment (chemotherapy) are acutely toxic to rapidly dividing cells such as sperm-producing cells. Depending on the chemotherapeutic agents used and the duration of treatment, spermatogenesis can sometimes recover after chemotherapy is stopped, but, unfortunately, in many cases, the damage is permanent. Prior to undergoing chemotherapy, therefore, it is strongly advised that sperm be frozen for preserving fertility. For more information, see my section on Fertility Preservation.

Other drugs such as opioids, many psychotropic medications, cimetidine, spironolactone and ketoconazole can impair spermatogenesis.